Need to Find These Manuscripts

Hadith Compilation by the Companions of the Prophet

Orientalists and western scholars often argue that Hadith

compilation started only in the 3rd century hijri.

This certainly is not the truth.

There exist several forms of evidences for Hadith

compilations by different companions of the Holy Prophet, may Allah bless him,

and their pupils.

A well known companion of the Holy Prophet, may Allah

bless him, named ‘Abdullah bin ‘Amr bin al-‘As (d. 63 A.H.) had prepared a

manuscript with narrations he directly listened from the Prophet. The

manuscript is famous by the name, ‘Sahifa al-Sadiqah’

He

embraced Islam in the year 7 AH a year

before his father did, Amr ibn al-'As. The prophet Muhammad used to

show preference to Abd Allah ibn 'Amr due to his knowledge. He was one of the

first companions to write down the Hadith, after receiving permission from Prophet

PBUH. Abu Huraira used to say that Abd Allah ibn 'Amr was more

knowledgeable than him.

His work Al-Sahifah al-Sadiqah which contained over

thousand ahadit, remained in his family and was used by his grandson 'Amr ibn

Shu'ayb. Ahmad ibn Hanbal incorporated the whole of the work of Abd Allah ibn

'Amr in his voluminous book Musnad Ahmad ibn

Hanbal thereby covering up for the missing Al-Sahifah

al-Sadiqah which was written in the days of Prophet Muhammad.

Mujahid said: I saw a manuscript with

Abdullah bin ‘Amr bin al-‘As so I asked about it. He said: “This is al-Sadiqa

and in it is what I listened to from the Messenger of Allah, may Allah bless

him, in it (means narrations therein) there is no step between myself and the

Prophet.” (Ibn Sa’d’s Tabaqat al-Kubra

Darul Sader ed. 2/373)

Abu Rashid al-Hurani said: I went to

‘Abdullah bin ‘Amr bin al-‘As and I said to him: “Narrate to me what you

listened from the Messenger of Allah, may Allah bless him.” He handed me over a

manuscript and said: “This is what I wrote from the Messenger of Allah, may

Allah bless him …” (Musnad Ahmad,

Hadith 6851. Shaykh Shu’aib Arnaut authenticated it)

This was later passed on to his great grandson ‘Amr bin

Shu’aib (d. 118 A.H.)

Although the book is not available today, but reference

to the narrations are made by sevral scholars.

Hafiz Ibn Hajr has quoted that Yahya bin Ma’in

said: “When ‘Amr bin Shu’aib narrates from his

grandfather through his father it is from (that) book.” (Tahzib

al-Tahzib 8/49).

2- Manuscript of

‘Ali:

Sayyidina ‘Ali (d. 40 A.H.), may Allah be pleased with

him, also had a manuscript of Hadith with him.

‘Ali, may Allah be pleased with him,

said: “We have not written anything from the Prophet except the Qur’an and what

is in this manuscript …” (Sahih

Bukhari, Hadith 3179)

Various narrations throw light on the contents of this

manuscript. It had injunctions on, “Blood-money,

Qasas, releasing of captives.” (cf. Bukhari, Hadith 111), “Sanctity of Madina” (cf.

Bukhari, Hadith 3179) etc. And ‘Ali, may Allah be pleased with him, used to

keep it tied with the scabbard of his sword (cf. Sahih Muslim)

3- Compilations

of narrations of Abu Huraira:

Al-Hassan bin ‘Amr said: I mentioned a

Hadith to Abu Huraira which he did not acknowledge. I said, “Verily I have

listened to it from you.” He said, “If you got it from me then it must be

written with me.” He held my hand and took me to his home and we saw many books

of Hadith of the Messenger of Allah, may Allah bless him, then we found the

Hadith. So he said, “Indeed I told you if I narrated it to you then it is

written with me.” (Jami’ Bayan al-‘ilm,

Hadith 422)

One may say this Hadith contradicts the narration from

Sahih Bukhari in which Abu Huraira himself said that he did not write the

Ahadith. Abu Huraira did not record the Ahadith in writing during the lifetime

of the Holy Prophet, but later he recorded

them.

As per the narration recorded by Ibn Sa’d, Abdul ‘Aziz

bin Marwan (d. 80 A.H.), the father of ‘Umar bin Abdul Aziz, wrote to Kathir

bin Murrah al-Hadharmi:

“At Hums you have met seventy of the

companions of Messenger of Allah who fought at Badr … Write to me what you have

heard of the Ahadith of the Messenger of Allah from his companions, except

those of Abu Huraira for they are with us.” (Tabaqat al-Kubra 7/448 Entry: Kathir bin Murrah)

This proves Abdul Aziz bin Marwan had the Ahadith of Abu

Huraira, may Allah be pleased with him, in written form with him. And it

further proves that efforts were being made to put the Ahadith in writing

during the time of the companions for certainly many companions lived even

after 80 A.H. when Abdul Aziz died.

4- Manuscript

of Anas bin Malik:

Anas bin Malik (d. 92 A.H.) had his own manuscript of

Hadith which he copied from the Holy Prophet, may Allah bless him:

Ma’bad bin Hilal says: When many of us

were with Anas bin Malik he came to us with a manuscript saying, “I heard this

from the Prophet, may Allah bless him, and so I wrote it and presented it unto

him.” (Mustadrak al-Hakim, Hadith 6452)

This shows companions started making private Hadith

collections right during the lifetime of the Holy Prophet, may Allah bless him.

5- Books of Ibn

‘Abbas:

Another well-known companion Ibn ‘Abbas (d. 68 A.H.), may

Allah be pleased with him, had multiple treatises:

Musa bin ‘Uqbah said: “Karib

bin Abi Muslim put in front of us a camel load or equal to a camel load of

books of Ibn ‘Abbas.” (Ibn Sa’d’s Tabaqat al-Kubra 5/293)

6- Manuscript

of ‘Abdullah bin Mas’ud:

Abdullah bin

Mas’ud (d. 32 A.H.), may Allah be pleased with him, also had his own

manuscript.

M’an said: ‘Abdul Rahman bin ‘Abdullah

bin Mas’ud came to me with a book and swore, “Verily my father wrote it with

his own hand.” (Jami’ Bayan al-‘Ilm wa

Fadhlihi, Hadith 399).

7- Manuscript of

Samurah bin Jundub:

Another famous companion, Samurah bin Jundub (d. 58

A.H.), may Allah be pleased with him, and also had his collection of Hadith:

Ibn Hajr writes:

“Suleman bin Samurah bin Jundub

transmitted a large manuscript from his father.” (Tahzib

al-Tahzib 4/198)

8- Manuscript of

Jabir bin Abdullah:

Jabir bin Abdullah (d. circa 70 A.H.) is also reported to

have made a manuscript of Hadith with narrations on Hajj.

Consider the following narration from one of his famous

students.

“Mujahid narrated from the manuscript of

Jabir.” (Tabaqat al-Kubra 5/467)

9- Compilation

of Bashir bin Nahik:

A student of Abu Huraira, Bashir bin Nahik also compiled

the Ahadith he learnt from Abu Huraira:

Bashir bin Nahik said: I used to write

whatever I learnt from Abu Huraira. Then as I intended to part from him I came

to him with the book and read it to him and asked, “This is what I heard from

you?” Abu Huraira said, “Yes.” (Sunan

Darmi, Hadith 494. Shaykh Hussain Salim Asad graded the report as Sahih)

10- Mauscript

of Hammam bin Munabbih:

Another student of Abu Huraira, Hammam bin Munabbih (d.

132 A.H.) made a collection of the Ahadith he learnt from Abu Huraira. All

praise be to Allah, it is extant to this day. Dr. Hamiddulah, an erudite

scholar of recent times, found two manuscripts of it in Berlin and Damascus and

published it. It has 138 Ahadith. Imam Ahmad has quoted all these narrations in

his Musnad. During my visit to Dr. Hamidullah in 1976 I had seen a copy of this manuscript.

From the nine famous students of who had written ahadith from Hazrat Abu

Huraira the only manuscript survived was this one.

This shows

that the recording and compilation of ahadith was going on in the life time of

the Prophet was on an individual basis like that of the holy quran. Ahadith

started being compiled on a state basis during the time of Umar ibn Abdul Aziz.

Islamic Manuscripts and Books

The arts of the pen and the book in the Islamic world have always excited the admiration of neighbouring civilizations, as is testified by many splendid collections in the Western world. In spite of the work of generations of scholars, the riches of most collections remain largely unexplored.

Islamic Manuscripts and Books offers the modern scholar a series of volumes that will cover subjects as varied as paleography, calligraphy and codicology, manuscript illustration and illumination, the history of typography, lithography and the printed book, the theory of manuscript cataloguing, catalogues of collections of manuscripts and rare printed books, the history of collections, and text editions that reflect a special awareness of manuscripts as physical objects.

Islamic Manuscripts and Books offers the modern scholar a series of volumes that will cover subjects as varied as paleography, calligraphy and codicology, manuscript illustration and illumination, the history of typography, lithography and the printed book, the theory of manuscript cataloguing, catalogues of collections of manuscripts and rare printed books, the history of collections, and text editions that reflect a special awareness of manuscripts as physical objects.

(Good Reading)

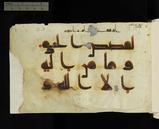

al-Qurʼān (MS Add.1125)

Fragments of a Hijazi Qurʼān probably written in the second century A.H. / eighth century A.D., containing verses from the Quran; Sura al-Anfāl (سورة الأنفال)al-Qurʼān (MS Add.1116)

Fragments of an Abbasid Qurʼān from the 3rd century A.H./ 9th century A.D. ( before 262/876), containing verses from the sura Āl ʿImrān (سورة آل عمران). The script seems to correspond to the Abbasid Style D.I as described by F. Deroche. The note added at the top of the folios states that this Qurʾān was an endowment of the governor of Damascus Amajūr.

Fragments of an Abbasid Qurʼān from the 3rd century A.H./ 9th century A.D. ( before 262/876), containing verses from the sura Āl ʿImrān (سورة آل عمران). The script seems to correspond to the Abbasid Style D.I as described by F. Deroche. The note added at the top of the folios states that this Qurʾān was an endowment of the governor of Damascus Amajūr.

Whenever anyone thinks of the art of Islamic Spain it is usually the great architectural monuments which come to mind; the Alhambra must be as familiar to most Europeans as the Parthenon. Yet the Muslim craftsmen of Islamic Spain—Al-Andalus—were equally skilled in the arts of metalwork, pottery, woodcarving, tilework and—as the museums of Spain and Europe testify—the art of manuscript illumination.

The production of manuscripts was always a thriving concern in Islamic Spain, but never more so than during the 10th and 11th centuries, when Al-Andalus probably boasted the highest literacy rate in Europe. The great Dutch historian of Muslim Spain, Reinhart Dozy, declared that during the days of the Andalusian caliph 'Abdul-Rahman III (912-961), nearly everyone could read, and although doubtless this was an exaggeration, it is fair to assume that the country contained an unusually large percentage of literate people. Certainly book-collecting was one of the passions of the times. Both 'Abdul-Rahman and his son Al-Hakam II (961-976), amassed huge libraries. The son's library is said to have numbered 400,000 works, with the catalogue alone filling 44 volumes and many of the works lavishly decorated by the scribes, gilders, printers and binders.

The Koran, of course, as the Holy Book of Islam, was richly embellished. By the 11th century most Korans began and ended with double pages of decoration and contained elaborate surah-chapter-headings and marginal embellishments. The opening and terminal pages were geometrical in character, usually based upon a circle within a square. They frequently included floral and vegetable motifs and the total design was enclosed within a knotted or interlaced border.

Unfortunately, knowledge of Andalusian manuscript illumination is limited; for large quantities of books suffered wholesale destruction in Spain on numerous occasions. Orte such time, according to the 19th-century Spanish historian Don Pascual de Gayangos, was in 1499, when Cardinal Ximénez de Cisneros burned a veritable mountain of Arabic manuscripts in Granada (on the assumption that anything written in Arabic had to be a Koran and therefore a danger to "the faith.")

Perhaps this wide destruction accounts for the strange absence today of western Arab-world manuscripts containing miniatures such as those commonly seen in Turkey, Persia and India. In fact, only three are known to have survived. One is a copy of the treatise on astronomy by Al-Sufi (died 986); the second is a 13th-century love story titled after its hero and heroine "Bayad and Riyad," and the third is a book of fables, "The Consolation of the Sovereign," illustrated by a Morisco in the 16th century.

Even with the Korans it is often difficult to establish an Andalusian origin. Because of the close cultural ties with Morocco prior to the end of the 16th century there was constant interchange of population and it is difficult to decide whether an "Andalusian" Koran was actually written in Spain or whether it was written in North Africa by an Andalusian refugee—especially since the first to leave the conquered Kingdom of Granada were the noble families and the well-to-do, the natural patrons of the arts.

But as the art declined in Spain, it flourished in North Africa wherein the 17th and 18th centuries painters turned their attention to many other works. Prominent among these was a well-known collection of prayers and devotions called Dala'il al-Khayrat, "The Indications of Grace," composed by Muhammad bin Sulay-man al-Juzuli, who died in 1465. This work offered much greater possibilities to the illustrator, with as many as 60 illuminated pages, including paintings of Mecca and Medina and an elaborate genealogy of the Prophet. One of the earliest copies of this work was made in 1639 and at one stage belonged to the famous historian of Islamic Spain, Don José Conde (1765-1820), who inscribed his name in Arabic on the cover: "The owner of this book is Yusuf Antun Qunday. May God lengthen his days!"

The designs adorning religious manuscripts, however, were more than mere decoration. Attempts to create an ideal symmetry also indicate the feeling of a divinely ordered universe as if the artists were reflecting the perfection of the Almighty's plan as revealed within the sacred scriptures.

Although printing and lithography appeared in the Arab world in the 19th century, many manuscripts were still written and illustrated by hand, particularly prayer books and Korans. Illumination endured into the 20th century—as can be seen in the opening pages of a little book of prayers written about 1910 either in Morocco or Rio de Oro. But this must have been one of the last manuscripts to be so produced. Today it is an extinct art.

- Islamic Manuscripts That Muslims Scholars need to retrieve study and publish, as valuable scholastic works have been lost or preserved in different European Libraries and archives.

(Privileged to view Many Manuscripts during my Trip to Italy 2018).

Italy houses 439 Persian manuscripts in two public archives and thirty public libraries located in fifteen different cities. All of them have been catalogued by Angelo Michele Piemontese (1989).

Bologna University Library

For

much of the millennium before the rise of Portugal and Spain, Venice flourished

as the hub of Europe's trade with the lands to its east and south. The profound

mutual influences that resulted have inspired multiple scholars and historians

to cast fresh looks at Venice and its history during pre-modern and modern

times, as a meeting point for commerce and culture, especially with the Muslim World.

Through

binoculars, I can barely make out the palm trees, gazelles, camels and other

Middle Eastern images on the Palazzo Zen, ancestral home of one of the most

prominent Venetian families involved in diplomacy and trade with the Islamic

world.

Three more manuscripts are preserved at the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies at Villa “I Tatti” in Florence, which, besides the three bound codices, possesses some loose folios from Persian manuscripts as well. Paintings in Persian manuscripts from the Harvard University Center (the Berenson collection) have been studied byRichard Ettinghausen (q.v.) in 1962, and their description is given by Piemontese (1984a). Additionally, within Vatican City, 189 Persian manuscripts are preserved at the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (hereinafter the Vatican Library): 158 are part of the Vatican collection, 23 of the Borgia collection, 6 of Barberini collection, and 2 of Rossi collection. These manuscripts were catalogued by Ettore Rossi (1948).

The Vatican Library also owns an important collection of Persian religious dramas (taʿzia). This collection was acquired by Enrico Cerulli (q.v.) during one of his sojourns in Iran in 1950-54 as the Italian ambassador. It was catalogued by Ettore Rossi and Alessio Bombaci (1961) and includes 1055 manuscripts, of which 15 are in Turkish, and a few others are written in both Turkish and Persian. Finally, 13 Persian manuscripts are part of a collection, mostly Arabic, purchased by the Vatican in 1927 and known as the Sbath collection, so called after the Syrian priest, Paul Sbath (1887-1945), whose original name was Bulos Sbāṭ al-Soryāni al-Ḥalabi, and who himself was a collector of manuscripts. Persian manuscripts of the Sbath collection were described by Piemontese (1978).

Apart from the Vatican Library, other Italian libraries that own the

larger number of Persian manuscripts are: the Medicean-Laurentian Library in Florence (83 MSS); the Library of the University of Bologna

and the Library of the National Academy

of the Lincei in Rome (60 MSS each); the

Marciana National Library in Venice (46 MSS); and the Ambrosiana Library in

Milan (37 MSS).

In fact, Persian manuscripts preserved in Italy are parts of larger

collections of Oriental codices which, starting in the Renaissance period, were

acquired for different reasons by various Italian courts, or through the

initiative of noble families, religious institutions, and important members of

the Catholic church, as well as individual scholars and travelers. The

geographical dispersion of the manuscripts, which had been usually kept in

Oriental funds without any linguistic distinction (except for the funds of the

Vatican Library), has been a major obstacle for identifying and cataloguing

them (for an updated report on the localization of Islamic manuscripts with

references to the published and unpublished catalogs see Heine for the Vatican; and Orsatti, Pirone, and Gallotta for Italy).

It was also in Rome, during the late 16th and early 17th century, that an important initiative led to an interest in collecting Oriental manuscripts in general, including the Persian ones. Under Pope Gregory XIII (1572-85), the printing house ‘Stamperia Orientale Medicea’ was founded by Cardinal Ferdinando I de’ Medici (1549-1609, Grand Duke of Tuscany from 1587) in order to print texts that could be used in promoting Catholicism among Muslims, and for refuting the rites of Eastern Christians. In 1586 Ferdinando I de’ Medici acquired a collection of more than 100 Oriental manuscripts, including some Persian, from the Jacobite Patriarch Ignazio Neʿmat-Allāh Aṣfar of Mardin

It was also in Rome, during the late 16th and early 17th century, that an important initiative led to an interest in collecting Oriental manuscripts in general, including the Persian ones. Under Pope Gregory XIII (1572-85), the printing house ‘Stamperia Orientale Medicea’ was founded by Cardinal Ferdinando I de’ Medici (1549-1609, Grand Duke of Tuscany from 1587) in order to print texts that could be used in promoting Catholicism among Muslims, and for refuting the rites of Eastern Christians. In 1586 Ferdinando I de’ Medici acquired a collection of more than 100 Oriental manuscripts, including some Persian, from the Jacobite Patriarch Ignazio Neʿmat-Allāh Aṣfar of Mardin

Gerolamo Vecchietti

purchased in Cairo the most remarkable Persian manuscript preserved in Italy—a

copy of the Šāh-nāma dated 30 Moḥarram 614/9 May 1217

(Florence, National Library, MS Magl. III.24; Piemontese, 1989, no. 145), which contains the first part of the epic only. The

manuscript, identified and described by Piemontese (1980), is the earliest

known dated manuscript of Ferdowsi’s

poem, and it was used as the basis for the critical edition of the Šāh-nāma by

Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh (8 vols., New York, 1988-2007; see also idem, 1985-86,

I, pp. 380-81; II, pp. 31 ff.). The manuscript has been reproduced in Tehran

both in facsimile (Ferdowsi, 1369 Š./1990) and as a typeset edition (Ferdowsi,

1996-98, 2 vols., publication still continues at the time of writing this

article).

In 1602 Vecchietti brought

from Hormuz a copy of Asadi-Ṭusi’s (ca. 1000-1072/73, q.v.) Persian lexicon

entitled Loḡat-e fors,

which is dated to 733/1332-33 and is

preserved in the Vatican Library as MS Vat. Pers. 22 (Rossi, 1948, pp. 49-51).

This manuscript was used as the main copy in Paul Horn’s edition of the text

published in Berlin in 1897 (Horn).

An important group of Persian manuscripts in the Vatican library

comprises 29 codices brought from the East by Pietro Della Valle (1586-1652, q.v.). These manuscripts have been

preserved in the Vatican since 1718 and were identified as part of the Vatican

collection by Rossi (1948, pp. 12-13). This group of manuscripts includes

copies of the works of Persian classical poets, such as Neẓāmi Ganjavi, Saʿdi, Ḥāfeẓ

(Della Valle was the first who introduced Ḥāfeẓ in Europe;

Portuguese and Safavid

forces in 1622 for gaining control over islands in the Persian Gulf. These texts are the Jang-nāma-ye Kešm (MS Vat. Pers.

30; Rossi, 1948, pp. 56-57; published by Bonelli), and the Fatḥ-nāma (Modena,

Biblioteca Estense, MS γ.F.6.22; Piemontese, 1989, no. 216; Pudoli, 1985;

Pistoso; published by Pudioli in 1987-88). Another poem by Qadri Širāzi

entitled Jarun-nāma speaks about the Safavids taking the

island of Hormuz (Jarun) back from the Portuguese; it is preserved in the

British Library in London as MS Add. 7801 (Rieu, II, p. 681).

Most of the Persian

manuscripts preserved in the Bologna University Library come from the

collection of Oriental manuscripts (mainly Arabic and Turkish) acquired by the

scientist, Luigi Ferdinando Marsili (or Marsigli, 1658-1730), during his participation

in the wars against the Ottomans in Europe (surrender of Buda in 1686 and the

siege of Belgrade in 1688). Besides scientific works, which must have been the

primary interest of the collector, this group of manuscripts also includes

literary texts (mainly copies of the Pand-nāma attributed to

Farid-al-Din ʿAṭṭār), an interesting poetic anthology.

Among the Persian manuscripts preserved in Venice, the following bear

larger importance: several scientific

works (mainly medical); works of classical Persian literature (the Pand-nāma,

the Golestān of Saʿdi, divān of Ḥāfeẓ, and

poems of Jāmi); an early copy (allegedly dated to early 14th century) of Balʿami’s (q.v.) translation of the

history of Ṭabari

No comments:

Post a Comment